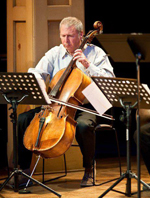

Interview with Louis Richmond, former cellist with the Argenta Trio Conducted by Forrest Hartman

Age: 70 City of Residence: Seattle, WA Years with Argenta: 1968 – 1970

Forrest: Where did you grow up? Louie: I grew up in Philadelphia? Forrest: Were you always into music? Louie: My uncle was a violist, a good amateur violist, and my aunt was an amateur violinist. It was assumed by my parents that I would go into music. It wasn’t that I was forced, but that’s what I was going to do. It was really that simple. Forrest: Were your parents musicians? Louie: No. They just had a real appreciation for music, and it was a noble calling type of thing. You could be a doctor, lawyer or a musician… So, I started to play the cello when I was 6. Forrest: That seems like a tough instrument to tackle at a young age. Often, people start with piano and then move to a stringed instrument. Louie: The reason why I started cello is very simple. I went to a concert of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and a cellist by the name of Gregor Piatigorsky was the soloist. He was a very, very big man, tall; and he walked out with his cello above his head. I thought it was so cool that people applauded for him before he did anything. It was weird. He just walked out on the stage and everyone applauded. Because of that, I thought I would play the cello. Forrest: Did you take to it right away? Louie: Yes. It wasn’t easy, obviously. I mean I practiced a long time. But I never wanted to play the violin or I never wanted to play the viola or I never wanted to play a wind instrument or a brass instrument. I really liked the cello. Forrest: As a child, were you one of those kids who had discipline and wanted to practice on your own? Louie: No. No. Not at all. It’s funny because my wife and I were talking about that today. When I was practicing, I would sneak out on the roof of our house and play wire ball with some of my friends down on the street. It was a two-story house. My mother would always call up. She always called me Louis, and she would say, “I don’t hear you playing.” I would say, “I’m working on fingering,” and I would be on the eve of our roof playing ball. I was a regular kid. Forrest: I imagine there was some point when you got serious. Louie: Yes, when I was 13 because I needed an instrument. I had a small instrument; like a half-size and then a three-quarter size cello. When I was 13, for my bar mitzvah gift basically, I got a cello. I’m still using the same cello. Forrest: It must have been a pretty nice instrument for a 13 year old? Louie: Yes. It was. It’s not a major Italian instrument or anything like that. Now, it’s a 100-year-old German cello. It’s a good instrument… So, that was kind of cool. When I was 13, I got my cello, and I still have the same instrument. Forrest: Is that the one you played through your entire professional career? Louie: Yes. That was my only instrument. Forrest: Did you ever find yourself wanting to buy a more expensive cello? Louie: Yes. It’s kind of a funny story. One of my most important teachers was a man named Lorne Munroe. He was the first cellist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and then he moved and he became the first cellist of the New York Phil. He was a major cello player. He had a great, old Italian instrument, a Gofriller, and somehow or other when I played it, it never sounded good. And when he played my cello, man, it really sounded good. I know that sounds silly, but I said to myself, “I don’t have the money to spend to buy a really great instrument. So, maybe I should just practice and make my instrument sound better.” Forrest: Sounds like a smart idea. Louie: I thought so at the time. It would be great to have a great cello just for economic reasons for “my estate” and all that, to pass it on. But I honestly don’t think – and it sounds like heresy – that I would be a better cellist if I had a better cello. Forrest: That makes sense. Let me ask you a little about high school. You said you became really serious about music at age 13, so you must have played in school. Louie: Yes. I played in the orchestra, and I played solos with the orchestra. That was a big deal then. The orchestra was pretty good. There was a pretty good music director. I wasn’t with my cello teacher, Lorne Munroe, then, but I was with a very, very good teacher, a man by the name of Orlando Cole. He was the cellist in the Curtis String Quartet. I studied with him when I was 13 at the New School of Music in Philadelphia. He was a great cellist, and it was alright to be a musician in my school. You didn’t have to be a football player. You could carry the cello after school. I was in a high school fraternity and everybody knew me as the cellist. As I said, I played solos almost every year, a concerto with the orchestra. Forrest: These days, it seems like band kids get teased or looked down on by their peers. That didn’t happen at your school? Louie: No. I went to a very academic school where about 90 percent of the kids went to college. We didn’t have great sports teams, but they were fine. It was alright to be a musician. There wasn’t a stigma like in some schools today. Forrest: Did you play sports as well? Louie: Yes. I played JV tennis. I had a little stint in Little League baseball when I was younger. I played sports, and I did other things. It wasn’t that cello was my only thing, but that was my major thing. Forrest: You went to some pretty impressive universities, the Eastman School and Temple. Can you tell me why you selected them and talk about your time there? Louie: I went to Eastman because it was considered a great music school, but the summer before Eastman I went to study in Puerto Rico. That was at the International Congress of Strings in San German, Peurto Rico… When I was in Puerto Rico, the cello teacher was Lorne Munroe. I knew who he was, obviously, because of his ties to Philadelphia. He overwhelmed me as a teacher, but I already had a commitment to go to Eastman for a year. I went, liked the school but did not like my cello teacher. He was a French cellist with a different style of playing, and we just didn’t connect. In music, your teacher is the most important thing you have really. So, I spent a year at Eastman, and I went back to Philadelphia. Lorne Munroe, at that time, was not on the faculty of Temple University. I asked him if he would teach me, but I needed to go to school. He became an adjunct professor at the school, and I was his only student. Forrest: So, he basically became a professor for you? Louie: Yes. He did. In fact, my son’s name is Lorne, so he was a very influential man. I studied at Temple, and I had a great undergraduate experience. It was really fun. The orchestra was great. Chamber music was wonderful. So, I studied with him, and I got my bachelor of music degree from him. Forrest: It was in cello performance? Louie: Yes. It was a bachelor of music in performance. Instead of writing a paper, you had to do recitals. Forrest: Did you go on and get a master’s? Louie: Yes, and I did summer music festivals in between. I went to Tanglewood one summer. I was the Bach cellist there. Then, I went to Dartmouth for a summer. I had just great summer experiences. But right after Temple, I got into the National Symphony in Washington, D.C., which was really kind of exciting. I was young. I was only 21, 22. I spent two years there, and I taught down there at a conservatory also. But I realized that in the National Symphony I was one of 12 cellists. Throughout my college days, I was one of one. So, I played solos and people cared for my opinion. Now, I was the youngest member of the symphony and I was just one of 12. No one ever asked me what I thought. “Gee was this the right tempo?” or this and that. Of course, they can’t. You know, it would be anarchy. There were 100 people in the orchestra. What I found was playing in an orchestra, as good as the National Symphony was, didn’t fulfill what I wanted. I was never good enough to be a great soloist. I couldn’t concertize around the world like a Yo Yo Ma or an Itzhak Perlman. I was good, but I wasn’t that good. So, I decided I wanted to go back to get my master’s in music. I went back to Temple… When I was there in Philly, I also started to teach a lot, and I actually got a job teaching at Dickinson College in Carlisle. I would fly out there one day a week, and from morning until late afternoon teach cello, then fly back to Philadelphia. I also did a lot of jobbing in Philadelphia, a lot of records, a lot of clubs. It was the typical freelance musician sort of lifestyle while getting a master’s degree. Forrest: When you talk about playing clubs, was it big band-style music? Louie: Yes, big bands that had string players in there. Sometimes there were two cellos, sometimes there were four cellos. They played for name acts. This sounds funny, but Jerry Lewis headlined the first professional club date I played. Jerry Lewis was singing then. It was strange, but this is a long time ago. We’re talking about 1966, ’67, ’68, around then… After getting a master’s degree, someone like me then looks to teach at colleges. There were all sorts of opportunities on the East coast, but I wanted to leave the East coast because my wife and I knew that if we stayed on the East coast we probably would get divorced because of parent problems. This was during the Vietnam War. We were hippies. I had a beard and all that sort of stuff. We decided, “Let’s go out West. We’ve never been out West before.” Forrest: What do you mean by “parent problems”? Louie: It was just that time where we needed to be independent. I’m still married to my same wife, for 49 years now. We just needed to get out on our own, so I didn’t want to particularly teach in an Eastern college. Those were the days – it might sound strange – when there were a lot of college jobs around. You also didn’t need a doctorate. You needed a master’s. So, I heard about this job in Reno. I didn’t know anything about Reno… I got the job just through my audition tape. They never met me, and there was no Internet then. You just sent a tape. Forrest: You never flew out or anything? Louie: No. And I flew out to other colleges on the East coast… I just sent a tape off to Reno with recommendations. I had good recommendations, and I’d played around a lot. I got the job. Forrest: Coming to Reno must have been a leap of faith for you since you didn’t no what you were getting into. Louie: Yes, and in all fairness, they didn’t know what they got into. I was an East coast musician: Jewish, liberal, anti-war with a beard. This was a long time ago in Reno when Joe Conforte was ruling the roost. They didn’t know me, and I didn’t know them. I actually drove out West in my VW Bug with my dog to look for a place to stay. My wife and our son, who was 2 or 3 then, stayed back East. They stayed in the basement at my parent’s house. I spent three days driving across the country with my cello, my dog and my VW Bug. It was very crowded. Forrest: What did people think when they met you? The city is still pretty conservative, so I imagine it was really conservative then. Louie: I’ll tell you a funny story… One of the big issues during the time period I was in Reno, while the war was going on in Vietnam, was that Joe Conforte was thinking of extending the bus line to Mustang Ranch, and that was bad. The second thing, and this was amazing to me because of my background and what I did, was that when the football team won, they were treated to a night at Mustang Ranch. This was the problem. One of the black football players decided he didn’t want to be with a black worker there, a prostitute. He wanted to be with a white woman. That caused a stir. That was the big news then. That was very strange to me. John Birch Society was very prominent. There were adds in the newspaper with skull and bones for fluoride. My very naïve peace sign on my VW Bug was stripped off my car all the time. It was a very different time. It was a very different environment for me… University of Nevada, Reno was like in a time warp to me, a real conservative time warp. Forrest: I imagine it was pretty hard for you and your wife to fit in? Louie: It really was. Everyone was very nice. I don’t want to say they weren’t. They were very, very nice, but I’m being candid. One of the faculty members said to another faculty member, “We really like the Richmonds. Louie is a good cellist and his wife is really nice, but we can’t have them over for dinner.” And the other guy asked, “Why not?” He said, “Because he’s Jewish. We can’t have any Jewish people over.” That was real strange to me. I wasn’t quite used to that coming from a professional. This was an academic. That was interesting. Socially, we had our friends, though. And this has nothing to do with the trio. (Violinist) Rusty (Goddard) and (pianist) Ron (Williams) were great. I stayed at Ron’s house when I got there, and he and his wife could not have been more accommodating. Everyone was trying to make me feel as comfortable as possible because, again, I was the odd guy out. You know, I was young, I was 25. I wasn’t from there, and everybody wanted me to feel very comfortable. I must admit I wound up teaching a lot, and it was great for me. The low guy on the totem pole teaches all the courses, and I learned a lot. It was a great two years. Forrest: Did you immediately become a member of Argenta? Louie: Yes, but it wasn’t called Argenta then. It was just called the University Piano Trio. That was my job. My teaching load was predicated on rehearsals and concerts for the trio. So, I was hired specifically as the cellist for the trio and teaching. Forrest: Did you three gel immediately on a musical basis. Louie: Yes. Once you start playing music, it’s music. I remember one of our first big concerts was the Beethoven Triple Concerto for piano, violin, cello and orchestra. We had to learn that. Then, we had a lot of concerts. Politics has nothing to do with anything once you start playing music. Forrest: What sort of repertoire were you doing at that time? Louie: The repertoire, to some degree, is limited compared to string quartets. There’s the traditional stuff. We did some romantic stuff and we did the classical stuff. We didn’t do a lot of avant-garde music. We did Debussy and we did Ravel but I don’t think anything more modern than that. Forrest: Was that up your alley? Louie: Yes. It was fine. I had a chance to conduct the musicians in more contemporary music when I wanted to. The repertoire was perfect. The pieces that are written for piano trio are absolutely superb. There just are not as many of them as for the string quartet. Forrest: As a group, how did you decide what you were going to play? Louie: I was the young guy, so I just listened. It was kind of up to them what they wanted to play. I was really excited that this was my full-time job and that I was getting paid to play great chamber music. I always played chamber music, but it was never in a regular environment where you’d rehearse almost everyday. Back East, you’d have a concert coming up in two or three months and you put together some music for it. Then, there’s another concert, and maybe you’re playing with other people. This was a regular thing. We played anything they wanted to play, and I was fine with that. It was great. Forrest: Is that also how musical decisions were made? Chamber music groups are interesting because there’s no conductor. How did the group run at that time? Louie: I think it ran just as any group would run now, to be honest with you… There was no one leader, so to speak. When I was a conductor, I was the boss and I said how fast things went and I said what we played and so forth and so on. It was a dictatorship. But this was a collaborative thing. Also, because I hadn’t played that repertoire, I was happy to do what they wanted to do… Ron and Rusty had another cellist before me, I guess. So, they knew the repertoire and I didn’t know it that way. They made the decisions, but they asked me, and I said, “Yes. That’s fine.” Forrest: Did you ever have differences of opinion? Louie: You always have differences of opinion, but you work it out… Let’s put it this way. There was never, that I remember, an issue where somebody said, “No. I’m not going to do that.” It was always, “Yes. That could work.” Any chamber music is a very collaborative sort of thing. That’s how it’s supposed to work. Forrest: It sounds like playing with the trio must have been refreshing after coming from the National Symphony. Louie: It was wonderful. Again, you were always one of 12 in the orchestra. You really had no say. This was a very mature thing to do for a 25-year-old. This was really cool. Forrest: In Reno today, there’s a pretty good classical music scene for a city of this size. What was it like when you were there? Were there strong audiences? Louie: No. There were very weak audiences. They had a series of maybe four or five concerts a year where people came from different cities all over the world. There was an orchestra that played a few concerts. But it’s hard for me to say what it was like because I had never lived in a city that small. You know, I lived in Philadelphia and Washington and I commuted to New York a lot. My summer experiences were at Tanglewood with the Boston Symphony or Dartmouth where there was a music festival. I always was around a lot of concerts and a lot of music all the time, and now I was the concert. That was cool in a way. I was the concert. Forrest: Was it tough not having other musicians to go see when you wanted to? Louie: Yes. It’s interesting that you bring that up because I haven’t thought of these things for a long time. I still wanted to study, so I went once a month to San Francisco. There was a cellist by the name of Laszlo Varga, a very, very fine soloist. I wrote him and said who I was and who I studied with and what I was doing and asked if I could study with him once a month. He said, “Yes,” so we would drive to San Francisco once a month with my cello and I would take a lesson from him. Forrest: The culture in San Francisco must have been refreshing. Louie: It was. San Francisco is really a cool city for a young couple coming from the East coast. It was very, very exciting. It was physically very beautiful also. So, we loved going to San Francisco. Forrest: Over the years, you’ve been involved in the formation of two orchestras, and I understand one of them was in Reno. Louie: Yes. What happened was we got there in September when school started and someone called me up in November, over like the Thanksgiving weekend, and asked me if I would be interested in playing in the clubs. I said, “No. I gave that up. I played in the clubs, and this is my job now.” He said, “We really need a cellist and we don’t want to have to fly someone in from San Francisco or Las Vegas.” I said, “No. I don’t want to do it.” They kept on offering me more money, and all it meant was going to one rehearsal and playing two or three shows. I said, “Yes. Alright. I’ll do it.” To make a long story short, I started to play in the clubs in Reno and Tahoe and a few times in Vegas. What was so intriguing to me was the musicians, the string musicians and the wind musicians, were really good and they were dying to play classical music but had no outlet. I was conducting the chamber orchestra at the university, and I had access to a music library, so I said, “I can bring some music during the breaks in the shows.” I said, “I’ll conduct if you guys want to play.” They said, “Oh yeah.” They wanted to play because they didn’t have a chance to play classical music. So, we started to play in the clubs in the band room in between shows, and they loved it. We kept on rehearsing and we got pretty good at it. So, we started an orchestra and we played concerts. I know that sounds strange and crazy in a way, but it was really that simple. I had access to the music, and I was just starting my conducting career. These guys and women really wanted to play, and it made sense. It was a blast. Forrest: Is this the same chamber orchestra that conductor Vahe Khochayan would end up running, the Reno Chamber Orchestra? Louie: I’m not sure. It might be. Again, it’s a long time ago. We played three or four concerts a year. Forrest: You called yourself, at that time, the Nevada Chamber Orchestra? Louie: Yes. Forrest: That’s a great story. Louie: It’s so silly in a way, but it does make sense. What was really interesting from a social standpoint is I started to play in the clubs on a regular basis. So, I had my university job in the daytime and my club job at night. I also played all summer at Tahoe. Some of my students called me Professor Richmond or Mr. Richmond in the daytime, and they were in the band at night and would call me Louie. It was very strange for me because I was young. I thought I gave that life of freelancing up, and I was this professor now. But at the same time, I was just one of the guys. We became socially friends with some of the musicians at the club who were also students of mine at the school. Forrest: It sounds like, throughout your career, you never had much trouble switching from pop music to classical to whatever they wanted you to play. Louie: It was pragmatic. You know, it was a way to supplement my income, and I knew that world from back East. As a freelance musician, you play what you’re asked to play. I played opera for five years in Philadelphia. I played ballet. I played for auto shows. I played for records. I just did everything. You’re a musician. That’s what you do. I felt very comfortable making the transition in Reno, although I didn’t want to at first. We would play for Glen Campbell and Liberace a lot, and sometimes there were four cellos on the stage. That’s a lot. These were big string sections. Forrest: Today, you help run a Seattle-based public relations firm. Most people would say, “That’s a departure from music.” Can you talk about your career change? Louie: I left Reno after two years because I really wanted a different place to teach. I came up and taught at University of Puget Sound, a small liberal arts college, which is great. I taught cello, and I conducted the chamber orchestra. It was wonderful. Then, I decided I wanted a professional orchestra. So, I left and I started a chamber orchestra called the Northwest Chamber Orchestra in Seattle. We played almost 100 concerts a year. It was a very successful organization. At that time, when I was conducting, I think it was the third or fourth most active chamber orchestra in the country. I did that for seven years. Then, there were problems with the board. You know, I didn’t get along with some of the members of the board and they didn’t get along with me. I left, and I stayed in music for a little while, but I was 40 and I really wasn’t making what I considered an adult living. Neither did my wife because she was a social worker. We were poor, and we had a kid. I said, “I’m changing careers,” and I decided I was going to go into public relations. Long story short, I got a job at a small luxury hotel doing PR. It was simply for economic reasons. I was very well known. Everyone knew who I was, but I wasn’t making any money and I was an adult. So, I changed careers. Forrest: Did you have any sort of educational background in public relations? Louie: No. You don’t need an educational background in public relations. You just need to know what an AP Style Book is. What happened is I was very, very lucky. I was hired by a European woman who thought it was really cool that I was conductor… She hired me, and I had no idea what to do. I was clueless. I said to myself, “Wait a second. I started two chamber orchestras. I had a lot of kids take my classes in school. If I can transfer those skills to public relations, maybe I can keep a job.” I remember the first day at work, they told me to do a marketing plan. I had no idea what to do, but I figured it out little by little. Forrest: Any regrets looking back? Are you happy with what you’re doing? Louie: That’s an existential question. I’ve come full circle now because I play my cello. I play a lot of concerts each year. People know me as the cellist again, and I love it. Would I have loved it this much if I had kept on doing it? Probably not. I’ll tell you an interesting story. I spent a year at the Parks Department in Seattle putting on concerts, and I brought some chamber orchestras to Seattle. One was the Paillard Chamber Orchestra, led by Jean-Francois Paillard, who was very well known at that time. He came to our house for dinner, and he was my hero. All he wanted to do was retire and sail. He didn’t want to play anymore. I’ve found that many musicians get burned out after awhile. So, I totally changed careers, and everything I did in music allowed me to be successful in public relations. I can explain that if you want. Forrest: That would be great. Louie: I had to do a lot of speaking for people. A lot of people find it hard to speak to people. I had to play Bach. That’s hard. Understanding Bach and Beethoven, that’s hard. Doing public relations is easy. I mean it really is. I taught a PR class at the University of Washington for three years, and I realized, “This is stupid. I don’t believe in it.” I quit. You don’t study PR in school. You study liberal arts in school, and then you work in PR if you want. So, here I am. I have this PR career, and it’s very successful I guess. I spent 10 years working for two hotels, and then I started my own firm. We still have the Sheraton, our first client, 21 years later, which is great. But I’m playing my cello again. Do I regret the career change? No. I don’t think I do because we have a nice lifestyle. We travel all over the world. We’re comfortable, I guess. We’re not rich, but we’re comfortable, and I still have my cello. So, I don’t regret it. Would I have liked to have done some other things? Maybe, yes, but I wasn’t great enough to be touring soloist. So, I’m pretty happy with how things turned out. Forrest: Even though there were decades when you didn’t make your living as a musician, did you keep playing? Louie: No. It’s very strange, and people keep on asking me why. I don’t have a good answer. I didn’t play for 25 years. Forrest: At all? Louie: I didn’t touch my cello for 25 years. People say, “Why?” The answer I’ve come up with, and I don’t know if it’s valid, is that it’s like being a boxer in a ring. If you don’t keep boxing, you get knocked out. I didn’t have time to practice in those beginning years to be honest with you. I was working literally seven days a week trying to figure out this new career. So, I didn’t make time to practice. Then, as the years came along, I got very involved in my career. Everyone knew I was a musician in the past, but I just never played. Then, I think I got afraid to play because I wouldn’t be any good. I think it was that simple. When I finally opened my cello up it was because of my oldest grandkid at the time. She didn’t know what a cello was. My son and his wife are great, but all their kids are really involved in sports, not music. It really frustrated me that they didn’t know what a cello was. That was my whole life… So, as my son took over the company more, I started to play the cello more. Now, I’m resigning my CEO title. My son’s taking it, and I’m going to be senior advisor. Do I regret anything? It’s dangerous to regret things. I’m real happy where I’m at. Forrest: How long did it take to get back in the swing of things as a musician? Louie: It took me about two years to get to where I felt like I could play in public again. It was painful. It was profoundly depressing. That’s when I regretted things. That’s when I said to myself, “Dammit. I shouldn’t have stopped playing.” I’m not where I used to be now, but for a 70-year-old, I’m not too bad. Forrest: Now, you’re practicing four or five hours a day. Louie: Oh yeah. I was practicing at 7:30 this morning… I play a lot of repertoire now. When I started again, I started in the community orchestra just to see what that was like, and that was horrible because they stunk compared to the National Symphony. Then, I played in the university orchestra, and they weren’t that good either. Then, I actually took chamber music classes at the university. As a senior you can do that. The instructor knew me from Philadelphia, which was kind of weird. The first concert I did was a Beethoven sonata. We played these recitals in the daytime, and my pianist is all of 18 or 19, and this old man walks out on the stage with her. Everyone’s trying to figure out, “What is he doing there.” Then, I did two other concerts: a cello duo with a young kid. That was really strange. I don’t do that anymore because I found a pianist and I began to play regularly with her. Forrest: I understand that one of your other enthusiasms is long-distance running? Louie: Yes. I’ve run 50 marathons. I just ran my 50th marathon in Portland. I wanted to wait until I was 70 to do it. I run a lot. I run about 50 miles a week. Forrest: To this day? Louie: Yes. I’m very lucky, but I run a helluva lot slower, that’s for sure. My dog is very frustrated, but I run a lot. Forrest: Do you find any similarities between music and running? Louie: The training. Training for a marathon is insane. It just takes so much time and it’s so physically and mentally draining. Playing a recital is physically and mentally draining also. The good part about both those things is you’re in control. When I run a marathon, I run for myself. I don’t compete. I mean, I’ve won a few races, but I’m not running against someone else. When I’m playing a recital, I’m not saying, “How would Yo Yo Ma play?” I want to be the best I can possibly be. I don’t want to be perceived as a cellist who stopped for 25 years and is playing again. That would be the worst criticism I could ever have. No one needs to know I stopped for 25 years. They’re coming to a concert. They’re hearing a concert. They’re expecting it’s going to be good. Forrest: I expect that running and music help you stay healthy. |

Name: Louie Richmond

Name: Louie Richmond